For years, building software meant translating ideas through multiple layers: an idea would move from a conversation to a document, from a document to tickets, from tickets to designs, and, finally, from designs to code. Execution was expensive, slow, and highly manual. The division of labor was also clear and evolved around managing that complexity. Product managers focused on defining what to build. Engineers focused on figuring out how to build it. Entire workflows existed to manage the gap between intent and implementation.

AI, along with low-code platforms is now breaking that model. Today, a rough idea can become a working prototype through prompts, templates, and AI-generated code. Product managers can turn conversations into structured requirements, flows, and priorities in minutes. Engineers can explore solutions before committing to architecture. Tools like Lovable, Bolt, and V0 let users describe what they want, and the system attempts to produce something specific you can click, test, and react to. Not a slide. Not a mockup. Something real. The practical result is simple: the distance between “I have an idea” and “here’s a working prototype” has collapsed.

Below, we will explore how AI-driven low-code platforms are rewriting the rules of software development and what it means for engineers and product managers.

The Democratization of Development

For decades, the boundary was clear: product managers defined problems, while engineers implemented solutions. Low-code platforms started to blur that boundary by making development more visual and accessible. Now, with AI entering the equation, we're witnessing something more profound - it makes technical capability more broadly available.

Product managers no longer need to fully specify an idea before seeing it. They can prototype basic functional applications themselves. Engineers no longer need to spend days on boilerplate and repetitive setup. They can focus on architecture, trade-offs, and the hard parts that actually differentiate a product. The barrier between conception and creation is now lower than it has ever been. That doesn’t remove the need for expertise, but it shifts where expertise matters.

How Is the Role of Engineers Changing?

For years, coding was about turning intent into syntax, but not only this. Engineering also involves understanding users, negotiating trade-offs, and anticipating consequences. AI automates most mechanical tasks now. As a result, the time spent coding decreases. Time spent thinking, reviewing, designing, and guiding goes up.

Specifically, now AI handles syntax translation almost instantly. It can draft boilerplate, implement basic functions, generate documentation, scaffold entire modules, generate tests, and refactor codebases that humans would rather avoid. The value of an engineer is no longer typing code. It’s deciding what the system should do, how it should behave under failure, where boundaries should exist, and what trade-offs are acceptable. AI is probabilistic. It works well when the logic is obvious. It struggles when systems are deeply interconnected, legacy-heavy, or high-risk. That’s why senior engineers matter more, not less. Security, scalability, performance, and complex integrations still require experienced engineers. So engineers are moving from “writing functions” to “shaping systems and guiding machines that produce code.”

There’s a side effect here that teams are already feeling. Senior engineers suddenly operate at multiples of their previous output because they know what “good” looks like and can steer AI effectively. Teams get smaller, while review and oversight become critical. But the tasks that used to train beginners are now automated. In this equation, juniors are the ones who struggle because the tasks they used to cut their teeth on - CRUD, tests, fixes - are the first things AIautomates. And this is where the fear shows up: If AI handles the junior-level work, where do junior developers come from? For the first time in decades, the talent pipeline feels unstable. Demand concentrates at the top, which is people who deeply understand systems, architecture, and integration. Full-stack thinking becomes even more valuable as AI blurs the boundaries between frontend, backend, and infrastructure.

A new skill also emerges: prompt generation. How engineers communicate with AI, how they structure instructions, and how they orchestrate multiple tools are becoming as important as writing the code itself. In many ways, prompt engineering is the new art of development.

So, AI isn't taking all dev jobs. But the role is changing dramatically and not into something less valuable. The job tilts toward architecture, system design, integration work, and orchestrating AI agents. Less “type code,” more “design the machine that writes it.”

AI will eliminate some jobs, especially junior roles. It will make strong devs incredibly productive, like “100x engineers.” It will force everyone to adapt, just like cloud, mobile, and the internet once did.

How Is the Role of Product Managers Changing?

Perhaps no role is being transformed more dramatically than that of the engineer. If engineers are shifting upstream, product managers are becoming more hands-on.

Traditionally, PMs lived in the gap between customer needs and technical implementation, sitting somewhere at the intersection of technology, business, and customer needs. Their job was translation: turning messy input into something engineers could build. They were defining the what and why of a product, then working closely with engineering teams to execute it.

AI and low-code platforms are allowing product managers to become builders themselves. A PM can now sketch a user interface, describe the desired functionality in natural language, and watch as AI generates a working prototype, internal tools, or even simple customer-facing features with minimal involvement from other specialists, such as designers and engineers. AI and low-code can get users surprisingly far for simple applications - dashboards, CRUD apps, basic workflows, and this is already happening.

Moreover, AI can analyze markets, competitors, and customer feedback, as well as transcribe meetings, assisting the product manager during the idea generation and validation phases. As a result, the boundaries between product management, design, and marketing are blurring. What previously required the coordinated work of an entire team can now be accomplished by a single person. PMs can test hypotheses directly with customers without waiting for engineering cycles. They can A/B test different user flows by building multiple versions themselves.

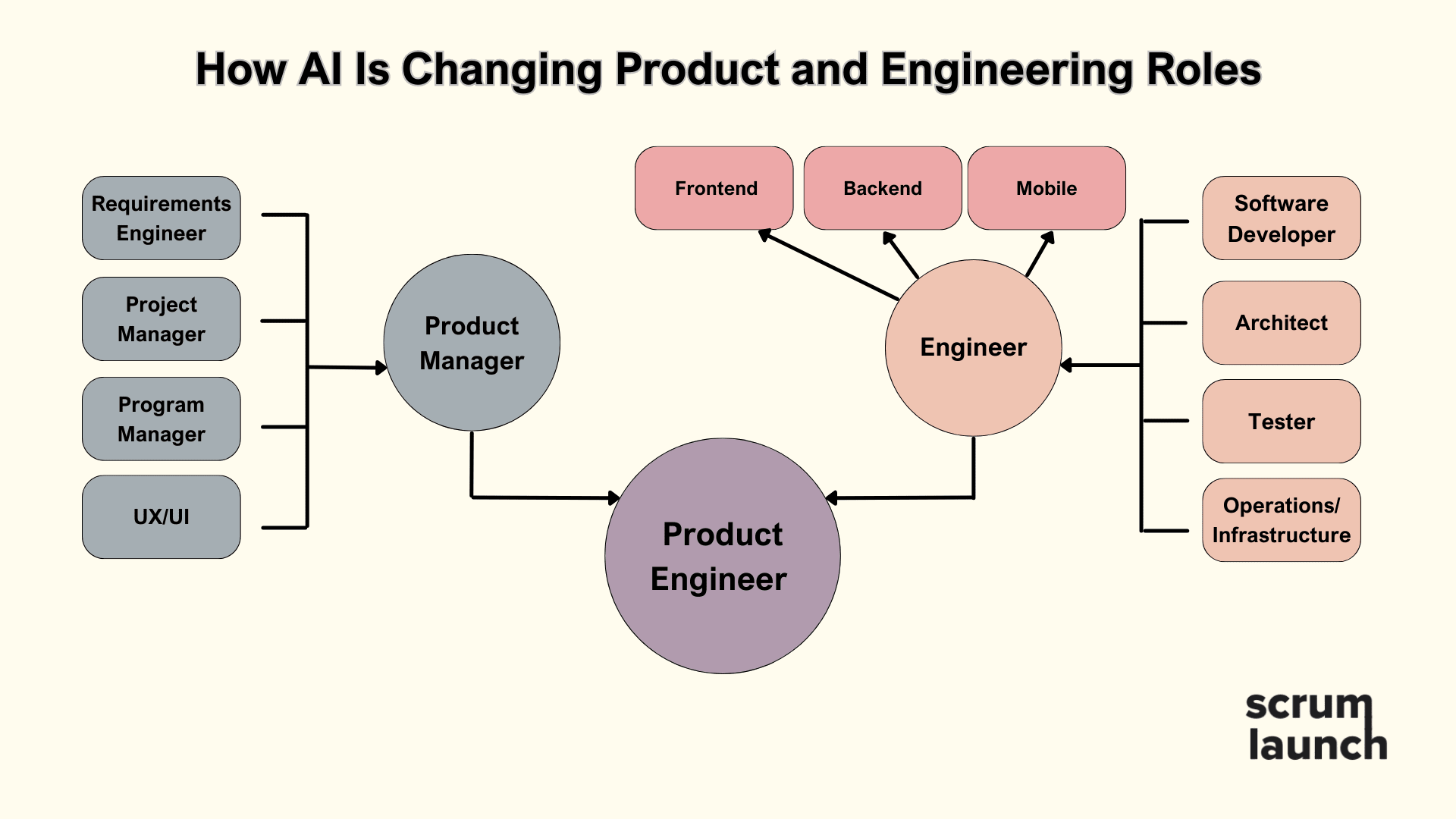

Many professionals increasingly describe themselves less as pure product managers and more as product engineers, noting that they now handle significantly more technical work alongside traditional PM responsibilities. Hybrid skills are no longer a bonus for product managers. Technical fluency, data intuition, and AI literacy are becoming the baseline for doing the job well. And this shift doesn’t stop at product management. Product owners and business analysts are moving in the same direction, where understanding systems and working comfortably with AI tools is no longer a differentiator - it’s the requirement of entry.

It doesn’t turn PMs into engineers. It changes when engineers need to be involved. PMs can validate core assumptions and user experience before consuming engineering resources. But while AI speeds up parts of the product management process, it doesn’t replace seasoned software engineers. Production systems still need deep engineering expertise. Performance, security, integrations, and long-term maintainability don’t disappear just because the first version was easy to build. So PMs need fewer engineers for early validation and simple tools, but still very much need them for anything production-grade or complex.

Hybrid roles

Product managers can now generate software more easily, handling early builds without waiting for engineering to realize their goals. But software engineers also need less product management. In small teams, engineers can ship entire features without formal PM involvement. As PMs become more technically capable and engineers become faster at exploring ideas, the line between the roles blurs. Many organizations are adapting. Some are forming “fusion teams” where PMs and engineers build together in real time. Decisions happen collaboratively, not through handoffs. Ownership shifts from “PM owns the what, engineer owns the how” to shared ownership of outcomes.

So, the overlap between product and engineering roles is real and it is accelerating. But this isn’t about eliminating roles. It’s about shifting where each role creates the most value. In early-stage startups, those boundaries can disappear entirely. One person, often called a product engineer, shapes the idea, prototypes the solution, and ships the first version.

Product engineering isn’t a new concept. Leading tech companies have used it for years to describe a model in which engineers and product managers work side by side, shaping the vision, defining solutions, and iterating quickly. What’s new is the scale. We’re seeing more technically fluent PMs who comfortably operate on both sides of the line. Teams are smaller, and for companies with limited budgets, this is a structural advantage. When PMs can spin up early versions using AI, companies don’t need to staff full engineering teams just to test ideas. Validation happens faster, with fewer people and less cost. That reality is already influencing hiring. Companies are increasingly looking for product managers with real technical depth - people who can move between defining the problem and shaping the solution, rather than handing it off.

In larger organizations, the roles don’t disappear, but they move up the stack. Either role can now handle the shared middle layer that once required constant coordination. That pushes PMs toward strategy, market positioning, and complex trade-offs. Engineers move deeper into architecture, system design, and the most challenging technical constraints. The “in-between” work can be handled by either.

New Challenges and Responsibilities

This transformation isn’t without complications. AI can generate code, automate workflows, and accelerate prototyping, but that doesn’t mean things are magically simpler. The easier it is to produce software, the more nuanced the responsibilities become.

First, there’s ownership and accountability. If AI generates a bug in production, who is responsible? The AI? The prompt? The engineer who accepted the code? The PM who spun up the prototype? None of those answers is obvious yet. Teams need new norms around review, testing, and responsibility. Without clear guardrails, speed stops being an advantage and turns into a risk. Fast feedback loops matter, but so do quality thresholds and human oversight.

Then there’s the challenge of maintaining deep technical expertise in an era where surface-level solutions are easier than ever to generate. Teams must resist the temptation to optimize only for speed and remember that some problems require careful, thoughtful engineering that can't be rushed. There’s also a very real debate about how far non-technical roles should go. Some experienced engineers believe that PMs touching the codebase with AI can turn into a multi-million dollar disaster. That sounds extreme, but the underlying point is valid. Production systems don’t break because of syntax. They break because of bigger structural decisions around architecture, integrations, performance, and security. The ability to make those decisions doesn’t come from prompts. It comes from experience, obtained through years of building, breaking, and fixing real systems.

And finally, as we already mentioned before, there’s the talent pipeline problem. AI automates the work that used to train juniors first. All the repetitive tasks that helped people build intuition are now auto-generated. If companies don’t decide on how engineers should learn now, there’s a risk of producing developers who are great at prompting but weak at systems thinking. Similar pressure applies to product managers. Technical literacy is no longer optional. Knowing how systems fit together, where things break, and what “good” looks like is now part of the job. Employees are expected to own more, and the stakes are higher. PMs are expected to build functional prototypes, and engineers to reason about product strategy. The tension at each role is growing, which can easily lead to burnout.

Market Change and Development of New Roles

It’s obvious that product development will accelerate thanks to rapid hypothesis testing and prototyping. At the same time, the number of people involved in product development will decrease, as specialists will possess more versatile skills in different areas. It leads to increased competition and market fragmentation due to a lower barrier to entry. Companies can now create simple, customized software for their own needs relatively quickly. At the same time, solo founders or small teams can build very specific products for a small audience and still make money thanks to AI. Business models may also change in this case: there will be more models with one-time payments instead of subscriptions, again due to the reduced cost of software development.

The decreasing barrier to entry in software development is leading to the need for programming skills even among those who are not developers. And such skills are needed not only by product managers; this trend is also affecting other professions. Similar shifts are happening in marketing, customer support, design, and analytics. Now it is important that specialists possess not only specialized knowledge but also technical skills, and can automate processes and create simple custom software to increase the efficiency of their work. Roles will increasingly intertwine and integrate. Each employee will take on more responsibility, resulting in the company structure becoming increasingly horizontal.

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, the impact of AI on the IT industry is becoming increasingly tangible, redistributing roles and changing internal company processes. Lower barriers to building software create new opportunities, but they also raise the bar on skills. Hybrid capabilities matter more than ever. Companies are increasingly looking for Product managers who understand technology, data, and AI workflows to move faster and make better decisions. They don’t just write specs - they test ideas, validate assumptions, and stay closer to reality. Engineers remain essential, but their role shifts away from repetitive implementation toward architecture, performance, security, and scalability - the hard problems AI can’t solve reliably. The future belongs to people who can think across boundaries: technically fluent PMs, architecturally strong engineers, and a growing class of product engineers who comfortably operate in both worlds.